A rather compelling reminder of the perils surrounding our food, our kitchens, and the entire journey of foodstuffs from field and barn to table and mealtime can be found nearly every day, while watching broadcast television.

In television production-studio kitchens, children as young as 8, and retirees in their 7th decade weave back and forth from the larders to their prep counters and pro-kitchen equipment, and from there to the ovens and stovetops, while competing to be selected as the best, by those persnickety and demanding celebrity chefs.

Vats of boiling oil, trays of broiling bacon, rotating mince blades, manual carrot chopping (fingernails in “claw” mode!), red-hot heating elements, grater surfaces, oven racks—these all can be focal points of danger and potential injury.

We watch as these intrepid and aspiring chefs, young and old, in the rush and turmoil of competing against both time and their highly skilled adversaries, inevitably back into each other while holding a hot vat or steaming kettle, or slice a digit or grate a fingertip or sear a knuckle, potentially dashing their hopes for the title of Master, Grand, or Top Chef.

On another channel in a fascinating recent documentary, about the early development of forensic science in New York City nearly a century ago, food contamination turns out to be the culprit in several very important court cases. For the first time in US history, meticulous testing and research were systematically used as legal evidence to prove accidental death, or intentional murder.

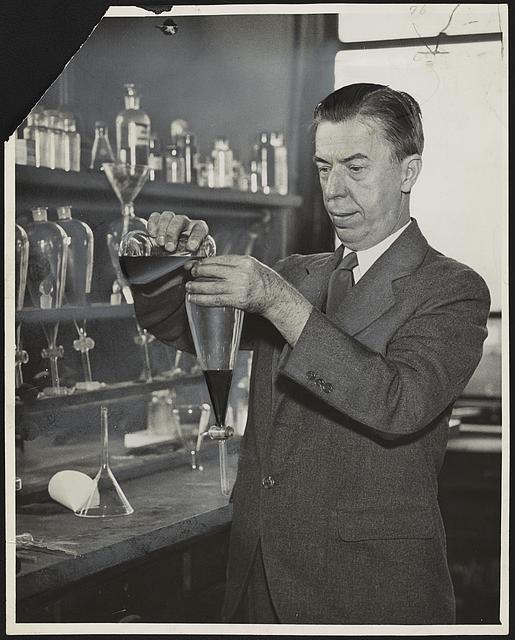

Dr. Alexander Gettler, first toxicologist and forensic chemist with the City of New York

Summer Barbecue Safety Can Be Tricky

It’s the heart of the summer, August 2016. We put wine-soaked cedar planks on our gas grills for salmon seasoning, load piles of charcoal into our Webers and Hibachis, we marinate our proteins and brush EVO on our pepper slices and zucchini filets, we make wonderful food and the aromas of char and caramelization swirl through our neighborhoods; and we, too, must be wary of the dangers. I remember an afternoon 50 years ago when my dad had a stubborn batch of charcoal and was sprinkling some grill lighter fluid on the smoking briquettes. Suddenly the tin can exploded in his hand. It was startling, but fortunately no injury resulted. Perhaps slightly wounded pride in having to explain to your son how not to use lighter fluid, as amply demonstrated. Have you seen or used those stand-alone whole turkey fryers? Check it out on Youtube, and you’ll see more examples of people breaching safety procedures when cooking outdoors. Hint: Do Not Immerse a Frozen Whole Turkey into A Vat of Boiling Oil.

These days, food manufacturers, and restaurants and chains, are very meticulous with their processes to protect the safety of their products, and their customers. And their customers’ customers. Still, accidents happen.

Indirect heating with heat transfer fluids has been common in industrial manufacturing, including food processing, for several decades now.

In 1968, a heat transfer fluid made of PCB (since banned for functional heating purposes, as well as most other uses) poisoned more than 1600 people in Japan, due to accidental contamination of edible rice oil.

We’ve Come a Long Way Since 1968

Food-grade heat transfer fluids are now very widely used in food manufacturing equipment, including high volume fryers, ovens, grills, dryers, and distillation applications; in the poultry, meat, dairy, baking and vegetable-oil processing industries.

Food-grade heat transfer fluids assure the consumer public, and the food production industry, that these crucial steps of these food-manufacturing processes are properly engineered, safe, and reliable.

Food-grade heat transfer fluids were originally registered and certified in the late 1970s by the USFDA and the USDA. Now, these certifications are maintained and managed by the NSF.

No food-grade heat transfer fluid has been more researched and more certified for safety than the Paratherm™ NF heat transfer fluid. In addition to its original certifications from the USFDA, the USDA, Canada H&W, and New Zealand MAF, Organism Laboratory Bioassay; and its current NSF registration and kosher and Halal acceptance, it’s the only product on the market that has been the subject of research into its inherent safety and toxicity after being used in a working process heating system manufacturing food products for several years.

In other words, not only has Paratherm NF held multiple certifications and passed toxicity standards as a brand-new, clear, unused fluid, it has also passed muster as a used, beaten up, moderately browned, yet still perfectly usable, still-within-specifications food-grade thermal oil.

We did these tests because no other food-grade fluid is used in more food plants and applications. Paratherm is the leader in this niche, in products, in service, in technical expertise, and we take the safety of the product very seriously, and intend to remain the leader.

So you can be assured, whether you’re specifying food-grade fluid for a new system, or have been using the same charge of fluid for 5 years, that it’s safe. Contamination aside, Paratherm NF continues to pass bioassay whether it’s new or used.

Paratherm also works with all its customers to maintain their systems, to test their fluids regularly, to avoid problems and prevent contamination as much as possible. Paratherm offers plenty of information on the web as well, to assist with safe handling and use of all of our products.